To keep this introduction to balance charts short, it assumes a familiarity with accounting basics. (KAG assumes that its readers know nothing of accounting.)

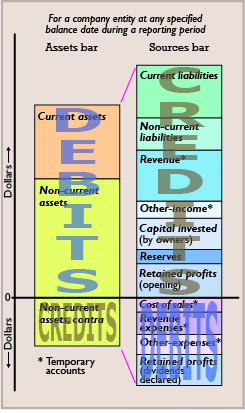

Figure 1: A balance chart representing a balance sheet and the definitions of debits and creditsAccounting is founded on the balance sheet equation, assets = liabilities + equity. This equation can be represented graphically, for example in the figure 1 balance chart. In balance charts the balance sheet equation becomes 'the net height of the assets bar must always equal the net height of the sources (of the money used to control the assets) bar'. The net height of a bar is its height above the x axis in dollars less its depth below the x axis is dollars.

Figure 1: A balance chart representing a balance sheet and the definitions of debits and creditsAccounting is founded on the balance sheet equation, assets = liabilities + equity. This equation can be represented graphically, for example in the figure 1 balance chart. In balance charts the balance sheet equation becomes 'the net height of the assets bar must always equal the net height of the sources (of the money used to control the assets) bar'. The net height of a bar is its height above the x axis in dollars less its depth below the x axis is dollars.

The height or depth of each box in the figure 1 balance chart represents the amount of money associated with the centre of interest for which the particular box is named. In this particular balance chart each box represents the balance of an account. An account is, as in literature, a story, and is the chronological story of amounts called postings becoming associated with and disassociated from the account's centre of interest. At any specified date (a balance date), the balance of an account (the total of all the postings to that account to midnight on the balance date) is represented in a balance chart by the height or depth of its box. That height is drawn to the y axis's monetary scale.

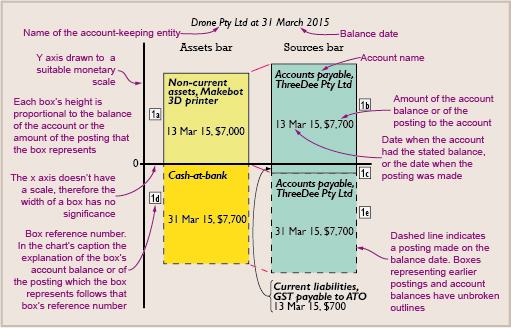

An entity's activities form a chronological series of events. An event consists of one or more transactions. Transactions are recorded in an entity's accounts using postings. A cash acquisition of say a 3D printer for $7,700 is one transaction. Were the same 3D printer acquired on credit, that event would be recorded as two transactions. In the first the acquiring entity takes control of the printer, in the second later transaction the acquiring entity pays the printer's seller. Figure 2 represents how the entity Drone Pty Ltd would have recorded that credit acquisition, and further explains balance charts. Figure 2: A balance chart representing the credit acquisition of a 3D printer which also explains the formatting of balance charts

Figure 2: A balance chart representing the credit acquisition of a 3D printer which also explains the formatting of balance charts

Balance charts can thus represent the financial state (called the financial position) of an entity and an entity's transactions. But balance charts can represent many other things including other financial statements, trial balances, performance trends, comparisons between entities, and budgets.

KAG uses balance charts and other types of illustration complemented by text to explain the basics of accounting. Readers will therefore understand accounting more easily, retain that understanding for longer, and thus find learning more rewarding.